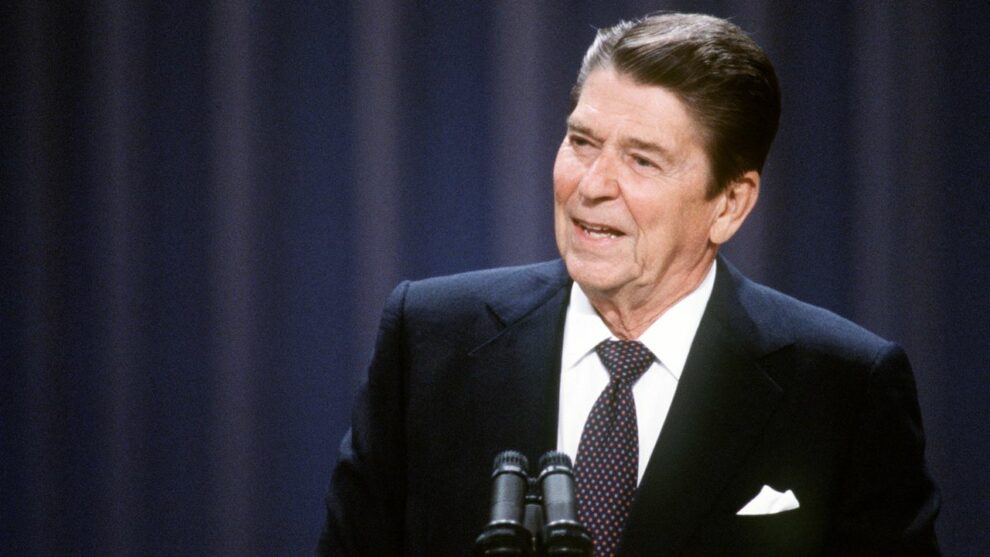

This week’s meeting at the Ronald Reagan Library in California between Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen and Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy is more than a convenient venue between Taipei and Washington, D.C. The location commemorates the presidency during which much of the U.S.–Taiwan partnership was first forged.

Indeed, despite the predictable caterwauling that is sure to come from Beijing, the Tsai–McCarthy meeting reflects four decades of continuity in U.S. policy. McCarthy would do well to recall that U.S. support for Taiwan is based in large part on the foundation that Reagan built.

Before becoming president, Reagan had traveled to Taiwan on two occasions. He believed the island to be one of America’s most vital allies in the region. In 1978 he described “South Korea, Japan, and [Taiwan] – all in alliance with the United States – forming a security shield in the western Pacific.”

Reagan saw these three nations as bulwarks against communist aggression – whether from Moscow or Beijing – in the Asia Pacific. He was also mindful of China’s unrelenting threat to Taiwan. In a national radio address the next year, Reagan cited a retired admiral that the island would fall unless it received “F-16s, harpoon missiles to stand off the Chinese navy and special anti-submarine equipment.”

Once in the White House, Reagan faced a problem. He inherited from his predecessors Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter the strategic embrace of China and sidelining of Taiwan, yet the United States had a mandate from Congress to support Taipei’s security.

Reagan also felt growing pressure from both China and his own State Department to jettison Taiwan and end all U.S. arms sales to the island. Doing so, he knew, would leave Taiwan easy prey for Beijing while eroding American credibility around the world. When a State Department memo recommending diminished support for the island arrived on his desk, a resolute Reagan wrote on it “We keep our promises to Taiwan – period.”

Instead, Reagan forged a strategic framework that preserved a stable relationship with China, reassured nervous allies in the region, and, crucially, locked in American support for Taiwan’s security. In the summer of 1982, after negotiating the “Third Communique” with China to ensure continued American arms sales to Taiwan, Reagan wrote a secret memo to his secretaries of State and Defense that codified an enduring principle.

While the U.S. remained committed to the peaceful resolution of cross-strait differences, “it is essential that the quantity and quality of the arms provided to Taiwan be conditioned entirely on the threat posed by PRC.” If the threat increased, so would America’s provision of weapons. Similarly, Reagan rejected China’s demand that he embrace the “ultimate objective” of ending American arms sales to Taipei. For Reagan, there was no room for ambiguity when it came to Taiwan’s security.

This framework accompanied the “six assurances” that the Reagan administration gave to Taiwan that same year. Those promises remain the bedrock of our political and security relationship today. They include: the United States would not set an end date for arms sales to Taiwan, nor would it consult with Beijing on such arms sales. The United States also committed not to take on any mediation role between Taiwan and the PRC, not to take a position regarding sovereignty over Taiwan, and not to pressure Taiwan to negotiate with Beijing.

That Reagan would provide Taiwan these political and security assurances was entirely consistent with his commitment to the freedom and security of the Taiwanese people. Throughout his presidency, he applauded Taiwan’s economic growth, supported its participation in international institutions, and helped midwife its transition from a military dictatorship to self-government.

Four decades later, Taiwan has become a robust democracy of 23 million free people, a $600-billion juggernaut economy, and the world’s foremost producer of advanced semiconductors. Reagan’s vision of what the island could become, undergirded by American support, is now what it is today.

At the same time, China has grown exponentially more powerful – and more menacing – since Reagan crafted his Taiwan policy. The U.S. commitments to Taiwan were always intended as a shield to deter Beijing’s aggression. Yet Washington still struggles to deliver the critical defense platforms needed to defend itself.

The very same F-16 fighters and harpoon missiles Reagan highlighted in 1979 remain almost 45 years later some of the most consequential examples of weapons still stuck in the $19-billion backlog of arm sales to Taiwan.

Reagan’s warning on Taiwan decades ago rings true today: “If we really want peace, we better remind the world of that America it seems to have forgotten, the one that stands by its commitments.” It is a compelling message — if today’s leaders are willing to listen.

Source : Fox News